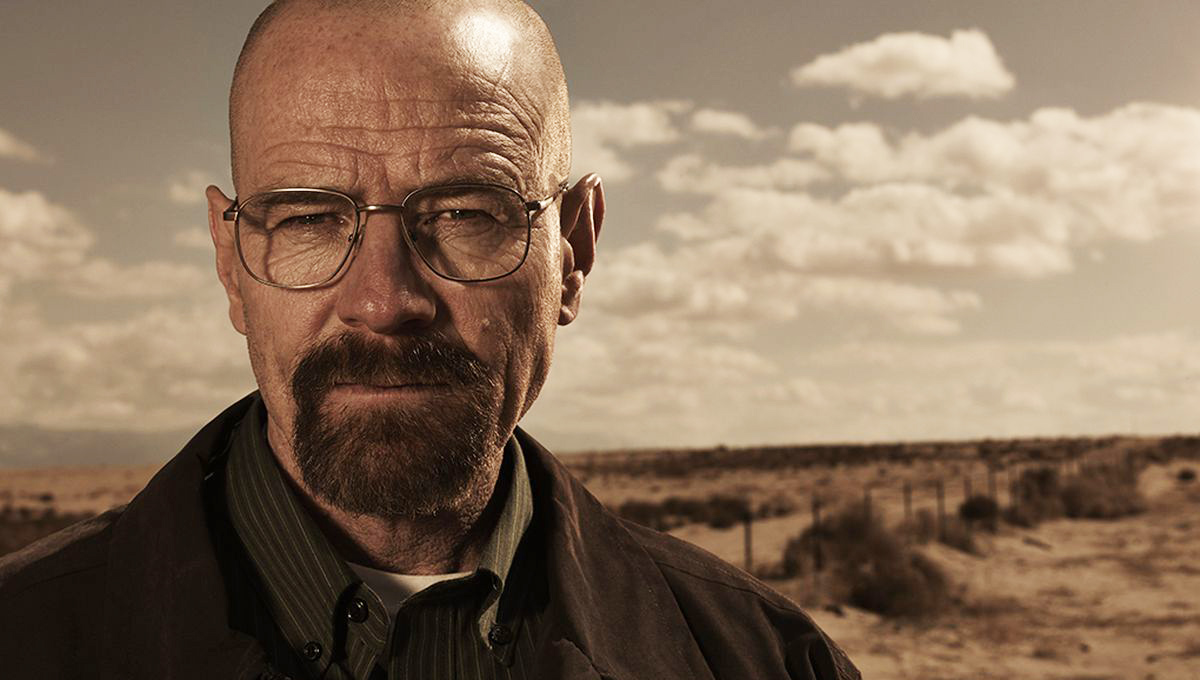

Bryan Cranston still remembers the exact second the Emmy statue felt real: not when his name echoed through the Microsoft Theater, but when the cold metal base kissed his palm backstage, heavier than any prop gun he’d ever hefted on Breaking Bad.

“It’s like holding a lightning bolt that’s been domesticated,” he says, eyes crinkling behind wire-rimmed glasses.

The win—for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Limited Series—was for The Studio, a razor-sharp satire about a Hollywood fixer who moonlights as a mushroom farmer in the Nevada desert. Cranston plays Saul Goodman’s spiritual cousin: a man who can green-light a blockbuster or a psilocybin harvest with equal aplomb.

The role was written for him by Jesse Armstrong’s successor, a 32-year-old wunderkind who’d binge-watched Malcolm in the Middle in quarantine and saw Cranston as “the only guy who can make corporate evil look like a hug.”

The script arrived on a Tuesday; Cranston read it on the porch of his Ojai ranch, cicadas drowning out the dialogue in his head. By page thirty, he was laughing so hard his wife, Robin, thought he’d finally lost it to method acting.

“The character’s first line is ‘I can get you an Oscar or an ounce—your call,’” Cranston recalls. “I knew I had to do it. Not because it was funny—because it was true.” The truth, he explains, is the quiet terror of reinvention: Walter White is dead, Hal is a meme, and at 68, Cranston refuses to be a nostalgia act.

The Studio let him play a man who weaponizes charm the way Heisenberg weaponized chemistry—except the product is ego, and the fallout is measured in box-office bombs and bad trips.

Filming wrapped in a decommissioned MGM backlot that still smelled like old money and older cocaine. Cranston’s co-star, a 25-year-old TikTok alchemist named Luna Vega, kept slipping him “microdose mints” between takes.

“She’d say, ‘It’s just for the glow, Bryan—think of it as craft services for the soul.’” He pocketed them like Tic Tacs, unsure whether to be flattered or terrified.

The Emmy nod came on a Monday; the win, on a Sunday that smelled like hairspray and desperation. When his name hit the teleprompter, Cranston’s first thought wasn’t gratitude—it was Don’t trip on the stairs, idiot.

His second was a flash of his father, a failed actor who died believing awards were for “pretty boys with capped teeth.” Cranston dedicated the statue to him in a whisper only the front row heard: “Dad, this one’s for the guy who taught me failure is just rehearsal.”

But the night’s real plot twist happened offstage, in a Vegas suite that looked like Elton John’s fever dream—gold-veined marble, a chandelier that could double as a UFO. Cranston had flown in for a victory lap: a quick Tonight Show spot, a steak at Bazaar Meat, and what his publicist billed as “a discreet celebration.”

Instead, he found himself in a penthouse with Luna, a sound healer named River, and a silver tray of psilocybin chocolates shaped like tiny Oscars. “I’d spent sixty-eight years saying no to everything fun,” Cranston says. “Figured one bite wouldn’t turn me into Timothy Leary.”

The mushrooms hit like a slow-motion car crash—first a giggle at the carpet’s paisley pattern, then a sudden, vertiginous clarity about his own face in the mirror. “I looked like a melted Ken doll,” he laughs.

“All that Botox panic for nothing.” The group had rented a karaoke machine; Cranston belted “Your Song” in a falsetto that made River weep into a bowl of truffle fries.

At 2 a.m., Luna asked the question that rewired his brain: “What if Walter White had just eaten the mushroom instead of cooking the meth?” Cranston’s answer—a rambling monologue about empathy as the ultimate high—ended up on someone’s phone and, by morning, in a Variety blind item.

He still cringes, but not from shame; from the realization that vulnerability is the only role he hasn’t overplayed.

Back in L.A., the Emmy sits on a shelf beside a jar of desert soil from the The Studio set—his own private reminder that trophies gather dust, but dirt grows things.

He’s already fielding offers: a Broadway revival of Network where Howard Beale trips on ayahuasca, a Netflix doc about actors who microdose for “emotional authenticity.” Cranston’s response is a shrug and a grin: “I’m not chasing the dragon—I’m just learning to ride it.”

The Vegas night taught him that the real award isn’t gold; it’s the moment the ego dissolves and you remember you’re just a guy from the Valley who once sold real estate to pay for headshots.

Robin found him at dawn on the balcony, humming “Tiny Dancer” to the Strip’s neon sunrise. “You okay?” she asked. Cranston nodded, eyes still wide as saucers. “I think I just won something bigger than an Emmy,” he said. “I won permission to be surprised.”

The mushrooms wore off by brunch, but the permission stuck. Now, when young actors ask for advice, he doesn’t talk about craft services or call sheets. He tells them to find a quiet room, eat something that scares them, and listen for the laugh that isn’t scripted. “That’s where the magic lives,” he says. “Not in the statue—in the stumble.”

News

She’s BACK! Amanda Bynes Unveils SURPRISE Romance—Fans STUNNED as Former Child Star Shares First Look at New Boyfriend After 2-Year Break From Love and Public Life!

Former Nickelodeon star Amanda Bynes is dating a new man. The 39-year-old former actress is seeing a business owner named Zachary, 40,…

Courtney Stodden’s SHOCKING New Look Revealed—Star Seen Leaving Plastic Surgeon Practically UNRECOGNIZABLE After Another Procedure! Internet EXPLODES With Reactions: ‘That Can’t Be Her!’

Courtney Stodden looked unrecognizable as she was wheeled out of a Beverly Hills plastic surgeon’s office on Wednesday. The reality TV siren, 31,…

FASHION SHOCKER: Dakota Johnson Flaunts Her Curves in Risqué Braless Gown—‘Naked Dress’ Look TURNS HEADS Before She Triumphs With Golden Eye Award at Zurich Film Festival!

Dakota Johnson had another ‘naked dress’ moment as she stepped out in a risqué lace gown at the 21st Zurich Film…

Lulu DROPS BOMBSHELL After Decades of Silence—Reveals Intimate Night With David Bowie! Fans STUNNED as Pop Icon Opens Up About Her SECRET Tryst With the Glam Rock GOD!

Lulu has confirmed for the first time that she did have sex with David Bowie as she shared intimate details from the…

Keira Knightley STUNS in Whimsical Floral Gown With Bizarre Lace Ruff—Fans GASP as She Shares Red Carpet LAUGHS With Glamorous Co-Star Hannah Waddingham at ‘The Woman in Cabin 10’ Premiere!

Keira Knightley was the picture of sophistication on Thursday night, as she shared a delighted embrace with co-star Hannah Waddingham at the premiere…

JUST IN: Lakers CUT Arthur Kaluma and SIGN Jarron Cumberland in Shocking Move! Meet the Team’s Newest Addition and Why He Could Be the Roster Wildcard No One Saw Coming!

The Los Angeles Lakers have made a strategic roster move that has caught the attention of fans and analysts alike,…

End of content

No more pages to load