The words detonated inside my skull a split-second before the first slap cracked across my cheek. My son’s hand—Robert, thirty-eight years old, the boy I’d carried through fevered nights and college tuition—rose and fell twenty times. Twenty. I counted every one, the way a drowning woman counts waves.

Carol, my daughter-in-law, laughed beside me, a bright, brittle sound that ricocheted off the suburban Queens kitchen tiles like cheap Fourth of July fireworks. The baked ziti I’d woken at dawn to layer—extra creamy, the way Robert begged for on every birthday since he was six—sat cooling between us, its cheese skin hardening into a lid over my humiliation.

That night, something inside me calcified. Silence wasn’t love anymore. It was slow-motion suicide.

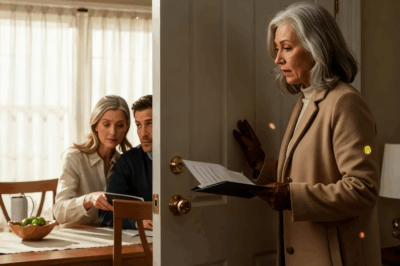

By sunrise they were gone—Robert’s SUV rumbling down the cul-de-sac, Carol’s heels stabbing the driveway like exclamation points. I waited thirty minutes, the old maternal radar still twitching for forgotten lunchboxes. Then I opened the nightstand, lifted the original deeds to the Forest Hills house—still in my name, never notarized despite Robert’s slick promise—and slid them into a briefcase older than he was.

George, my late husband’s poker buddy turned retired lawyer, answered his Queens row-house door in plaid pajamas and shock. My left cheek had ballooned purple; the right carried the perfect crescent of Robert’s college ring. George didn’t waste time on pity. He brewed coffee strong enough to strip paint, spread the deeds under his green banker’s lamp, and confirmed: “Legally, Olivia, this address is still yours.”

I touched the bruise, felt the throb sync with my pulse. “Sell it today. Cash. New locks before six p.m.”

George’s eyebrows climbed, but he saw the ice in my eyes and reached for the phone.

By noon I stood in a Midtown Manhattan notary’s office—subway brakes screeching thirty floors below like the city itself was exhaling. The Masons, a young couple flushed with first-home fever, handed over a cashier’s check that made my knees weak. I signed Olivia Margaret Russo with a steady hand I hadn’t owned in decades.

“Can you move in this afternoon?” I asked. Mrs. Mason’s eyes softened. “We can be there by four.” “Take the furniture, the dishes, the ghosts,” I said. “I’m traveling light.”

George drove me to Chase on Northern Boulevard. The balance glowed: enough to vanish, enough to plant new roots, enough to seed a women’s shelter I’d only read about in the Times. I wired the donation anonymously—New Dawn House, Asheville, NC—then bought a one-way Greyhound ticket at Port Authority. The clerk slid it across like contraband: New York to Santa Fe, departs 2:15 p.m.

I turned off my phone before the first ring could find me.

The bus hissed out of the Lincoln Tunnel, and Manhattan’s steel teeth receded in the rear window. Somewhere past Philly I finally breathed. Past Harrisburg the landscape loosened—cornfields, billboards for Cracker Barrel, a sky so wide it felt like forgiveness. Twenty-four hours later the high desert air of Santa Fe hit my lungs, thin and clean. Helen waited at the terminal, silver hair whipping in the wind off the Sangre de Cristos. One look at my face and she folded me into a hug that smelled of piñon smoke and decades of friendship.

I cried then—ugly, snotty, cleansing sobs—while adobe roofs caught the last gold of sunset.

Helen’s guest room became sanctuary. Nights I woke gasping, Robert’s palm print burning phantom heat across my cheek. Mornings I walked the dirt roads, boots crunching caliche, until the fear loosened its grip. Two weeks in, I turned the phone on just long enough to see the bank balance and a cascade of texts:

Robert: Mom, call me. This is insane. Carol: You’re evil. We’re ruined. Robert again: I’m sleeping in the CAR, Mom.

I powered down without replying. The maternal cord had been cauterized the twentieth time his hand met my face.

Helen and I pored over Asheville real estate listings on her ancient Dell. One listing stopped my heart: half-acre, 1930s farmhouse, wraparound porch, creek at the back fence, asking price a steal because the owner’s daughter lived in Raleigh and wanted her father closer. I made the offer sight-unseen. Accepted by sundown.

I bought seeds before I bought sheets.

The closing took seven days. On a crystalline October morning I signed the new deed under a notary who smelled of gardenias and Wite-Out. The realtor handed me keys still warm from the locksmith. I drove my thrift-store pickup—$2,800 cash, no credit check—down the Blue Ridge Parkway, windows open, Dolly Parton on the radio, wildflowers slapping the fenders like applause.

The farm greeted me with silence so complete I heard my own blood. I stepped onto the porch, set the briefcase on the swing, and whispered to the mountains: This life is mine.

I named the dog Popcorn the day he wandered up, ribs showing, tail helicoptering. I named the creek Mercy. I named every tomato plant after a woman I’d never met but whose story might one day echo mine.

Neighbors trickled in: the Johnsons with peach jam, Martha from New Dawn House with gratitude and a casserole. Sunday dinners became tradition—fried chicken, cornbread, stories swapped like baseball cards. I painted watercolors of the creek at dawn, sold them at the Asheville farmers’ market for gas money and pride.

I wrote at night, kerosene lamp hissing, Popcorn snoring under the table. Not a diary—testimony. Every slap, every laugh, every lock turned became ink. When the manuscript was done I mailed it to Helen’s editor friend in SoHo. Six months later Starting Over at 60 hit the remainder table at Malaprop’s Bookstore and somehow climbed the regional charts.

The launch night packed the store. Women clutched tissues; one gray-haired lady in a Panthers hoodie asked, “How did you find the courage?” I told her the truth: “First I found dignity. Courage followed like a stray dog.”

I was signing the last copy when I sensed him—Robert, gaunt, tie loosened, holding my book like a hymnal. Our eyes locked across the aisle. Helen tensed beside me, ready to summon security. I shook my head.

He approached slow, as if the floor might tilt. “You look… luminous,” he said, voice cracked from disuse.

I waited. No script for this.

He pulled a white envelope from his jacket. “It’s not much. First installment. I’ve been saving.” His fingers trembled. “I read it three times. I’m in a men’s accountability group. I… I get it now.”

I studied the man who’d once loomed godlike in my kitchen. He was smaller, eyes bloodshot but clear. “Keep the money,” I said. “Send it to New Dawn House. They need roofs more than I need penance.”

He nodded, swallowed hard. “Your farm sounds like Eden in the book.”

“It is.”

A beat. “Could I… see it someday?”

“Maybe when the peaches ripen.” It wasn’t forgiveness; it was possibility left on the table like an extra chair.

He left without another word. The bell above the door chimed once, soft as a closing prayer.

Two years later—my sixty-second birthday—another car crunched up the gravel. Same hesitant silhouette. This time he carried a small cedar box. Inside: my grandmother’s gold watch, the one I’d assumed lost in the purge.

“Found it in a drawer the Masons left,” he said. “Happy birthday, Olivia.”

I fastened it around my wrist. The second hand swept forward, steady as a heartbeat.

“I’m moving to Charleston,” he added. “New job, new start. Thought you should know.”

The porch creaked under our combined weight of history. Popcorn sniffed Robert’s shoes, deemed him harmless, flopped down with a sigh.

“I’m glad,” I said, and meant it.

No embrace. No cinematic tears. Just two survivors on a porch in the Blue Ridge dusk, fireflies igniting like slow-motion fireworks.

He drove away. I watched taillights disappear around the bend, then turned back to my table of women—Helen, Martha, the Johnsons, Elellanena fresh from the shelter—passing cornbread and second chances.

Later, under a Carolina moon bright enough to read by, I opened my notebook to a fresh page.

Starting over isn’t erasure, I wrote. It’s archaeology—digging through ruin until you strike bedrock, then building something true on top.

The creek kept singing. Popcorn chased a lightning bug. My watch ticked toward tomorrow.

And for the first time in sixty-two years, I danced.

The first winter on the farm arrived with a vengeance, wind knifing down from the Blue Ridge like a warning. I woke to frost on the inside of the bedroom window, the kind that looked like lace until you touched it and it melted into accusation. Popcorn burrowed under the quilt, his nose cold against my ankle. I brewed coffee strong enough to wake the dead, then stood on the porch in my late husband’s barn coat, watching the creek ice over in slow-motion calligraphy.

That was the morning the letter came.

Not an email, not a text—an actual envelope, heavy cream stock, postmarked Charleston, SC. My name typed in courier font, no return address. I carried it inside, set it on the pine table like it might explode, and only opened it after I’d fed the chickens and split kindling until my palms blistered.

Inside: a single sheet, Robert’s handwriting—smaller now, careful, like a schoolboy practicing penmanship.

Olivia,

The group leader says restitution begins with honesty. I owe you more than money. I owe you the truth I never told you.

I was drowning long before that Sunday. Carol had been cheating for a year. I knew. I pretended I didn’t because admitting it meant admitting I’d failed at the one thing I thought I was good at—being the man of the house. You were the easiest target. You never fought back. I hated you for it. I hated myself more.

I hit you because I was small, and you were the only mirror left that still showed me the size of my cowardice.

I’m learning to live in that smallness now. The apartment smells like bleach and regret. I cook for one. I walk the Battery at sunset and count the ships the way you used to count my fevers. I volunteer at the VA on Thursdays, reading to men who lost limbs in places I’ll never understand. Their stories make mine feel petty. Good.

I enclosed a check—$247.36. It’s every extra dollar from last month. I’ll send another when I can. Not to buy forgiveness. Just to prove I remember the weight of twenty slaps.

If you burn this letter, I’ll understand. If you cash the check, I’ll keep sending them until the debt feels lighter on my side of the scale.

Either way, thank you for the book. I keep it on the nightstand. Some nights I read the part where you describe the creek at dawn and I can almost smell the wet stones.

Robert

The check fluttered to the table like a white moth. I stared at it until the numbers blurred. Then I endorsed the back—Pay to the order of New Dawn House—and mailed it from the little post office in Candler where the clerk still called me “ma’am” like it was a prayer.

Spring exploded across the mountains that year, dogwoods flashing white against the green like surrender flags. My tomatoes broke records; Mrs. Johnson swore my Brandywines could win the state fair. I entered three jars of bread-and-butter pickles under the name Olivia Russo, Mercy Creek Farm and took home a blue ribbon the color of Robert’s eyes the day he learned to ride a bike.

The ribbon hung above the kitchen sink, catching sunlight every morning while I washed dishes and hummed Patsy Cline. Some mornings I caught myself waiting for the other shoe—waiting for Robert to show up drunk, or for Carol to slither back with lawyers and crocodile tears. But the only footsteps on my gravel were neighbors bearing casseroles, or Popcorn chasing squirrels.

Then came the knock that changed everything.

I was elbow-deep in biscuit dough when the screen door squeaked. Martha from New Dawn House stood on the porch, eyes red-rimmed, clutching a manila folder like a life raft. Behind her, a girl—no more than nineteen—hovered in the driveway, arms wrapped around her ribs as if holding herself together.

“Olivia,” Martha said, voice cracking, “this is Kaylee. She’s got nowhere else.”

Kaylee’s left eye was the color of storm clouds; her lip split like overripe fruit. She wouldn’t meet my gaze. I wiped flour on my apron and opened the door wider.

“Guest room’s made up,” I said. “Popcorn doesn’t bite, but he’ll steal your socks.”

That night Kaylee sat at my table picking at cornbread while Martha explained: boyfriend, ex-Marine, fists like cinder blocks. Kaylee had fled with nothing but the clothes on her back and a bus ticket paid for by a shelter in Knoxville. She was eight weeks pregnant.

I poured her sweet tea strong enough to float a horseshoe. “You’ll stay as long as you need,” I told her. “This creek’s got a way of washing things clean.”

She cried then—quiet, shoulders shaking. I didn’t hug her. Some wounds need air before they need touch.

Kaylee stayed six months. She learned to milk the neighbor’s goat, to can tomatoes, to laugh at Popcorn’s obsession with the mailman. When her belly swelled round as a harvest moon, I taught her to knit booties the color of mountain laurel. The night her water broke, I drove her to Mission Hospital in my pickup, hazard lights blinking like fireflies. I held her hand while she pushed out a squalling boy with Robert’s same cowlick.

She named him Creek.

After Kaylee moved into a tiny apartment in West Asheville—rent paid by New Dawn’s transitional fund—she still came Sundays for dinner. Creek learned to walk between the rows of my pole beans. Some nights I caught myself watching the road, half-expecting Robert’s car. He never came. The checks did—$187 here, $312 there—always with a Post-it: For the roof. For the babies. For you.

Year three brought a letter from the publisher: Starting Over at 60 had sold 10,000 copies, mostly to book clubs in Charlotte and church groups in Greenville. They wanted a sequel. I laughed so hard I scared the chickens.

I wrote it on the porch swing, Creek napping in a laundry basket at my feet, Popcorn snoring like a freight train. Roots in Concrete spilled out in six months—Kaylee’s story braided with mine, with Elellanena’s, with every woman who’d sat at my table trading nightmares for cornbread. I dedicated it: To every woman who thought sixty was the end. It’s just intermission.

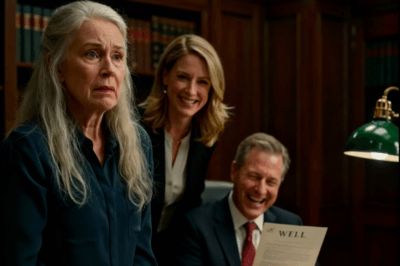

The launch was held at the Asheville Community Theatre because Malaprop’s couldn’t hold the crowd. I wore the blue dress I’d bought for my first date after the divorce—1968, with a boy who worked at the A&P and smelled like Vitalis. Helen teased me about cradle-robbing. I told her some things improve with age.

Robert was in the back row.

I spotted him the moment I stepped onstage—same gaunt cheeks, but his eyes held steady now, like a man who’d learned to sit with his own weather. He wore a corduroy jacket two sizes too big, sleeves rolled to reveal forearms tracked with faint white scars. Self-inflicted, I realized later. Old shame.

I read the chapter about the night Creek was born. When I looked up, Robert was crying without sound, tears cutting clean tracks through the dust on his cheeks. After the Q&A, the crowd thinned. He waited until the last fan left, then approached slow, hands open like a supplicant.

“I drove up from Charleston,” he said. “Didn’t know if you’d want me here.”

I studied him. The arrogant tilt of his chin was gone; in its place, something humble and terrifying—accountability.

“You read the new one?” I asked.

“Twice. The part where Kaylee names the baby Creek—” His voice cracked. “I sat in my truck and bawled like a calf.”

I gestured to the empty seat beside me. We sat in the dimming theatre, ghosts of applause still echoing.

“I’ve been sober eighteen months,” he said. “Group every Tuesday. I sponsor a kid now—twenty-two, fresh out of juvie. Hits his mom when he’s high. I tell him what I did to you. He thinks I’m making it up until I show him the book.”

I swallowed. “And Carol?”

“Married the guy from her office. They live in Alpharetta. Sent me a Christmas card with a Labrador puppy. I threw it away.”

Silence stretched, not uncomfortable. Outside, Asheville’s streetlights flickered on, one by one.

“I don’t expect anything,” he said finally. “Just wanted you to know the money’s still coming. And I fixed the fence at New Dawn. The one by the playground. Did it myself. Took three weekends.”

I pictured him on his knees in the Carolina clay, hammer in hand, sweat cutting runnels through sawdust. The image lodged behind my eyes like a burr.

“You hungry?” I asked.

He blinked. “Starving.”

We walked to Early Girl Eatery on Wall Street. I ordered shrimp and grits; he got the tomato pie. We talked about everything except the twenty slaps—his new job managing a hardware store, the stray cat that adopted him, the way Charleston sunsets reminded him of the creek at dusk. When the check came, he reached for it. I let him.

Outside, the air smelled of woodsmoke and impending rain. Thunder rolled soft over the mountains.

“I should head back,” he said. “Early shift tomorrow.”

I nodded. We stood awkward on the sidewalk, two strangers who shared DNA and a history of violence.

He pulled a small box from his pocket. “For Creek’s first birthday. If it’s okay.”

Inside: a hand-carved wooden boat, sails painted blue as the parkway in October.

“It’s beautiful,” I said.

He shrugged, embarrassed. “Therapy project. Sanded it for a month.”

I tucked it into my purse. “He’ll love it.”

Another silence. Then: “Olivia… I don’t know how to say I’m sorry in a way that sticks.”

“You already did,” I said. “Every fence post. Every check. Every Tuesday night you show up for that kid.”

His eyes filled again. This time I didn’t look away.

Drive safe, Robert.

He nodded, got into a dented Tacoma with South Carolina plates, and disappeared into the mist rolling down Patton Avenue.

I walked home under streetlights that haloed like grace. Popcorn met me at the gate, tail thumping a welcome. Inside, Kaylee had left a note on the fridge: Creek said “mama” today. Think he meant the dog.

I laughed until I cried, then cried until I laughed again. The sound echoed through the little house like church bells.

Spring again, the fifth on Mercy Creek. The peach trees exploded in pink so fierce the Johnsons swore they could hear color. I turned sixty-five under a sky the shade of Robert’s childhood bedroom walls, back when he still believed I hung the moon.

The party spilled across the yard: Kaylee chasing Creek through the sprinkler, Helen snapping photos with her ancient Polaroid, Martha unveiling a sheet cake iced with Starting Over at 65 – The Sequel. Robert manned the grill, apron reading Kiss the Cook (He’s Sorry), flipping burgers with the same hands that once bruised my face. The scars had faded to faint parentheses; his eyes held only light.

After cake, the kids (Creek and the shelter toddlers) hunted Easter eggs I’d hidden in the tomato cages. I slipped away to the creek, needing a moment with the water that had carried away so much grief. Robert found me there, two glasses of sweet tea sweating in his grip.

“Thought you might need this,” he said, handing one over.

We sat on the new bridge (plaque polished bright), feet dangling above the current.

“Got news,” he said. “The kid I sponsor (Jaden) just graduated the program. Starts community college in the fall. Wants to be a counselor.”

I smiled so wide my cheeks hurt. “You gave him the boat.”

He nodded. “Told him every storm passes. Some leave better timber.”

Silence settled, comfortable as flannel. Dragonflies skimmed the water; a kingfisher rattled overhead.

“I’m selling the Charleston place,” he added. “Buying the lot next door. Figured Mercy Creek could use a handyman in residence.”

My heart did a slow somersault. “You asking permission?”

“Nope. Just giving you veto power.” He bumped my shoulder. “Neighbors should get along.”

I studied the horizon (my horizon), peach blossoms drifting like confetti. “Build it small. And paint the door blue.”

He laughed, the sound rolling down the holler like thunder with no bite.

That night, after the last guest left and Popcorn snored on the porch, I opened my notebook to the final page.

Epilogue:

Some endings are quiet. No swelling violins, no slow-motion hugs. Just a bridge that holds, a watch that ticks, a dog that dreams. Just a woman who learned that starting over isn’t a single grand gesture; it’s choosing, every dawn, to water what grows instead of mourning what burned.

I am sixty-five. My hands smell of earth and peach jam. My table is never empty. My creek keeps its promises.

And if you’re reading this, wondering if it’s too late (it isn’t). The creek’s still running. There’s room on the bridge.

I closed the book, set it beside the blue-ribbon pickles, and stepped into the dark. Fireflies stitched the night shut. Somewhere down the road, a hammer would start at sunrise (Robert building his future, one nail at a time).

I lifted my face to the stars and whispered the only prayer I needed:

This life is mine.

And the mountains answered back.

News

Billionaire pushed his black wife into the pool to make his girlfriend laugh — until he learned who.

It began with a blaze of white light—an almost unreal glare pouring down from a sky so bright over downtown…

After returning from my trip, i found my belongings at the door and a message from my son: “sorry, mom. no space for you.” so i moved into my hidden apartment and froze the house transfer. at the family meeting, i brought my lawyer. no one saw it coming.

The suitcase hit the porch with a thud 💼 that echoed through my soul, its zipper half-open like a wound…

I ran to the hospital to see my son in intensive care. suddenly, the nurse whispered: “hide… and trust me.” i froze behind the door of the next room, my heart pounding. a minute later, what i saw made my blood run cold…

The fluorescent lights blurred into a streak of white fire as I bolted down the sterile hallway of New York…

My millionaire sister accidentally caught me sleeping under a bridge — homeless, exhausted, forgotten. after she learned my children had abused me, stolen my house, and thrown me out, she bought me a beachfront condo and gave me $5 million to start over. days later, my kids showed up smiling, flowers in hand… but she saw right through them. and so did i.

The rain hammered down like a thousand accusations, soaking through my thin sweater as my own son hurled my suitcase…

I was headed to the airport when i realized i forgot my late husband’s will. i rushed back to the house, but as i opened the door quietly, i overheard my son and his wife planning something chilling. i wasn’t supposed to hear it. but i did. and i…

The screech of tires on the slick Oregon asphalt yanked me from my holiday haze—I was halfway to Portland International…

My daughter-in-law said i’d get nothing from my husband’s 77 million. she sat all smiles at the will reading. but minutes later, the lawyer put the papers down… and laughed.

The room fell dead silent as my daughter-in-law, Rebecca, rose from her chair at the will reading in that sterile…

End of content

No more pages to load